The city has endured an unprecedented year and this could be an address like none before, an opportunity to instill hope and optimism among residents and business owners who have experienced painful losses of loved, and devastation to their finances.

By ELIZABETH CHOU | hchou@scng.com | Daily News

PUBLISHED: April 19, 2021 at 6:00 a.m. | UPDATED: April 19, 2021 at 6:33 a.m.

Tricia Helton, who worked as a manager for the homes of affluent Angelenos and celebrities, was hired more than a year ago to oversee the house of a Brentwood family.

After COVID-19 pandemic “Safer at Home” rules kicked in, that job went away. Without an income, the 48-year-old Studio City resident scrambled to pay her rent, and keep up payments on her car and credit cards.

She was no stranger to tough times; she spent some of her 20s homeless. “So I know how to make a dollar stretch,” she said. “(When times were good) if I had half a bottle of shampoo, I’d buy a new one. But now, I wait until it gets all the way down, and add water to it.”

Helton cut way back. She appealed to the car loan and credit card companies for extensions. But by the end of summer, she’d blown through her savings. She now owes about $9,000 in unpaid rent, and that could climb to $11,000 by the end of June.

“It’s been a lot harder to even have a normal life,” she said.

On Monday, when Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti delivers his State of the City speech, Helton is eager to hear some better news — not just for herself, but for all L.A. residents.

This could be an address like none before, an opportunity to instill hope and optimism among residents and business owners who have experienced illness, the losses of loved ones and devastation to their finances.

Helton has been reading the comments placed under the mayor’s Instagram posts in recent months, by people facing similar circumstances like hers. She knows she is not alone in her struggles. Results of the recent “quality of life” survey by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs bears that out. Nearly one-fifth of respondents said they’d lost their job during the pandemic; 40% saw their income decline.

The mayor’s state-of-the city address will be livecast on his Facebook page and Twitter account, at 5:15 p.m., repeating last year’s remote speech. A year ago, the mayor grappled with an uncertain future with his city in the grip of the outbreak. Now, many uncertainties remain, but with statistics indicating that the pandemic is easing, the path has begun to clear.

With most of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions being lifted statewide in June, the economy may soon have a chance to spring back to life. In his speech, the mayor would be expected to put forth his plans on the city’s recovery, and how leaders will handle the toll left by COVID-19, which has taken the lives of more than 23,000 people.

There is much more for the mayor to address. Angelenos’ anxieties endure about the availability and affordability of housing and the homelessness crisis, which preceded the pandemic, have been exacerbated.

Meanwhile, a reckoning around racial injustices is under way. The year was punctuated with mammoth protests over law-enforcement brutality, demonstrations that may kickstart in response to more recent killings of citizens by law officers and the anticipated verdict in trial of the policeman accused of killing George Floyd in Minnesota. Racial disparities have been further underlined by the disproportionately harsh effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities of color.

And framing the city’s comeback is a steadily recuperating, but still fragile, business climate.

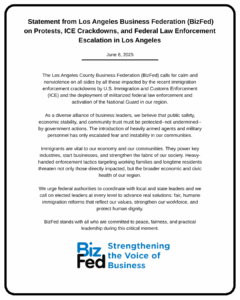

Tracy Hernandez, CEO of BizFed, said she expects to hear Garcetti discuss recovery measures for businesses that could include allowing restaurants to keep using the sidewalks to seat diners. She said that many businesses want to see streets cleared of homeless encampments.

And she expects an announcement on efforts to improve access to broadband internet connection. A year living of “staying home” has “shed light on telework, tele-health, tele-medicine and tele-education needs,” she said.

Garcetti could touch on the $1.3 billion allocation from the American Rescue Plan, approved by Congress in March. Part of those funds are expected to backfill pandemic losses, with the city anticipating a revenue shortfall of around $600 million this fiscal year. Many groups are also calling on city leaders to fund new relief and recovery initiatives.

Last week, dozens of community, civil rights and labor groups joined with residents to call on the city to direct the federal stimulus dollars toward a recovery plan for families affected by the pandemic. They presented a plan that laid out a proposal for investments in child and eldercare, job training for women, support for female-owned businesses, housing stability and rent relief, youth jobs and leadership, a guaranteed basic-income for high-need families, and reimagining ways to keep communities safe.

Admittedly, some Angelenos are pessimistic about the future. The UCLA study revealed that younger, white residents of Los Angeles County (which includes regions outside of the area Garcetti represents) were worried about their quality of life declining, and that they’d be unable to keep pace with cost-of-living increases.

Older residents share those fears. A 55-year-old San Fernando Valley resident, who asked to be anonymous to protect her ability to get a job, said that her age has made it difficult.

She left her office job several years ago. Now she competes against people who are trained in more current software. Her skills were less marketable, she said, and employers did not want to give her a chance to learn on the job, even though she’s a “quick study.”

She was forced to live in her vehicle, and then in a tent on a Valley street. She attended school to be trained in new software and graduated with honors, she said. People who meet her would not be able to tell she is without a home, she said.

From her vantage point — she’s currently living in a hotel room as part of a COVID-era outreach program — she expressed doubts about the ability of the the country to recover, much less the city. “I don’t know how people are going to get out of debt,” she said.

Another woman experiencing homelessness, who also asked to remain anonymous, said she wanted to hear Garcetti discuss initiatives to keep housing costs affordable.

Having known former lawyers, professional workers, and others living on the streets with her, she described homelessness as “the great equalizer.” She said she believes the many encampments spreading about the city, including the one at Echo Park Lake where she had been pushed out by city officials, is “opening people’s eyes, to understanding the complexity of this problem.”

Meanwhile, Helton who paid close attention to news of the federal stimulus package, said she wants to see more sincerity from city leaders, such as Garcetti, around serious matters, particularly people’s struggles with paying rent. She wants to see less of what she called “virtue-signaling” from politicians, efforts aimed at making officials look good but that have limited value for residents.

Helton’s example: She learned in March that the city will be using federal stimulus money toward providing $259 million in rental assistance. She was floored to learn the relief would be given out through a lottery. “I had to keep reading it, over and over, because I couldn’t believe it,” she said.

Helton said that for people like herself who had lost their jobs, to not know if there was a contingency plan for helping everyone affected troubled her. It was “not right,” she felt.

Several weeks ago, Helton said she had a “meltdown.” She found herself on the floor crying, “just screaming,” as she thought about potentially getting saddled with more debt. Helton, who grew up in Tennessee and also lived in Georgia, does not want to leave L.A., where she’s lived for more than two decades.

She came here to escape a tough background, the racist hatred she endured while living in the South. Because of her dark complexion, Helton was called the n-word by her adoptive family. Her Asian heritage — she is the child of a “war-bride” from Vietnam — spurred taunts pulled from movies such as “Full Metal Jacket” that cast her in sexual stereotypes.

In Los Angeles, “people are more open-minded,” she said.

Helton’s backup plan is a move to another state, where she could stay at a friend’s home. But it would not be easy.

“I don’t even need navigation to get around, because, you know, I’ve been here so long,” Helton said, apologizing as she fought back tears.

She would miss her neighborhood, the people she’s befriended at such places as the little local market and the postal shop. Even amid the toughest of times, it all adds up to home.

“The people that I talked to, whenever I go to like the little convenience store,” she said, “I’m never going to see them again.”